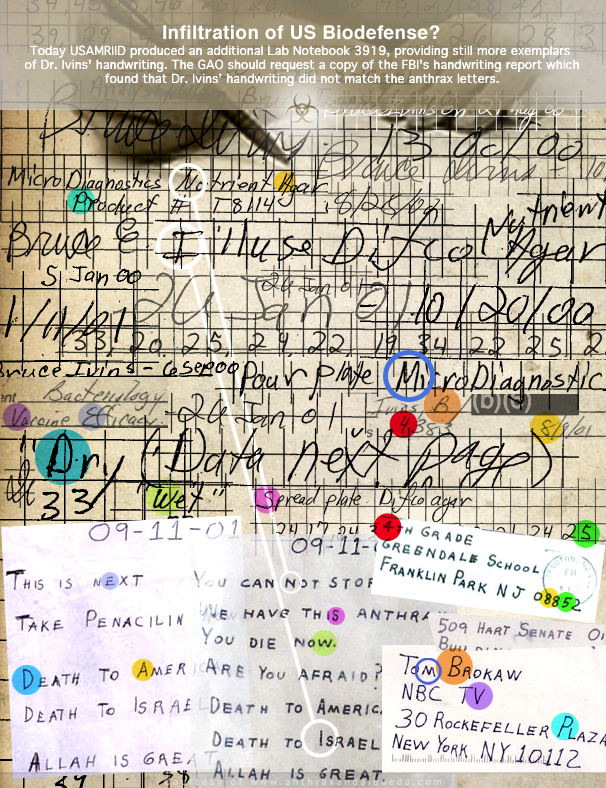

* Nonexemplary Conduct: Those Arguing That Dr. Ivins Was The Murderer Have Neither Produced Exemplars Of His Handwriting Nor Sought The Disclosure Of The Expert Reports

Posted by DXer on May 14, 2013

Posted by DXer on May 14, 2013

This entry was posted on May 14, 2013 at 3:46 pm and is filed under Uncategorized. Tagged: *** Dr. Bruce Ivins, *** FBI anthrax investigation, handwriting on anthrax labels. You can follow any responses to this entry through the RSS 2.0 feed. You can skip to the end and leave a response. Pinging is currently not allowed.

DXer said

Designation: E2290–07a

Standard Guide for Examination of Handwritten Items1

This standard is issued under the fixed designation E2290; the number immediately following the designation indicates the year of original adoption or, in the case of revision, the year of last revision. A number in parentheses indicates the year of last reapproval. A superscript epsilon (ε) indicates an editorial change since the last revision or reapproval.

http://portal.astm.org/EDIT/html_annot.cgi?E2290+07a

DXer said

Posted April 1, 2011

Handwriting Address Interpretation Software being used by the FBI

http://handwritinginstitute.com/handwriting-address-interpretation-software-being-used-by-the-fbi/

Handwriting Analysts International

Center for Scientific Handwriting Analysis Training and Research

***

Armed with a $428,000 grant from the National Institute of Justice in Washington, D.C., Srihari and his team are modifying the HWAI soft ware. The ultimate aim is to be able to provide foolproof analysis that can be used to support the testimony of handwriting experts in courts.

Scientific tools, such as those developed by Srihari, are considered essential for admitting handwriting evidence in U.S. courts due to a number of recent rulings, including the Jon‑Benet Ramsey case concerning expert testimony.

Though handwriting analysts may be able to solve the question of who penned a ransom note or forged a check, their testimony is not admissi ble as evidence in criminal cases. The reason being that since they are human, they cannot claim complete objectivity.

“A human expert may put in his or her own bias unconsciously,” explains Srihari. “We have built the foundation for a handwriting analysis system that will quantify performance and increase confidence in determining a writer’s identity.”

The software basically validates individuality in writing. The idea that everyone’s handwriting is different is taken for granted. Srihari has developed purely scientific criteria for that premise.

He has submitted a paper, “Individuality of Handwriting” to the Journal of Forensic Sciences. If accepted for publication, the paper will herald a new era in criminal cases, as it will form the basis for admitting expert testimony on handwriting under the so‑called Daubert guidelines set by the U.S. Supreme Court.

Srihari and his team developed the software by first collecting a database of more than 1,000 samples of hand writing from a pool of individuals rep resenting a microcosm of the U.S. population in terms of gender, age and ethnicity.

Multiple samples of handwriting were taken from subjects, who were asked to write the same series of sentences in cursive. Instead of analyzing the sentences visually, the way a human would, Srihari explains, the researchers deconstructed each sample, extract ing features from the writing, such as the shapes of individual characters, descenders, and the spaces between lines and words.

The researchers then ran the sam ples through their software program. “We tested the program by asking it to determine which of two authors wrote a particular sample, based on measura ble features,” recalls Srihari. “The pro gram responded correctly 98 percent of the time.”

Part of the software has been devel oped at CedarTech, a spin-off from Cedar. “Not all work that needs to be done in this area could be performed in a university setting,” Srihari notes.

Although he believes in conducting research for its own sake ‑ that is, with out necessarily exploiting the findings for commercial purposes ‑ Srihari feels that market‑driven research is far more satisfying because there is an ultimate goal.

“Some of the end goals are so chal lenging that it does not trivialize the science,” he concedes.

It was to meet these challenges head on that Srihari and his wife, Rohini, also a computer scientist, co founded Cymfony, a software company specializing in information extraction technology. Despite years of research, Srihari remains more of an educator than a scientist. He balances the day between his teaching job and what he calls “seri ous” commercial research.

“Pattern recognition is going to become a multibillion dollar industry and its applications are innumerable,” Srihari says. “We are just beginning to tap into this industry, and this what drives me.

DXer said

The FBI explains Professor Sargur Srihari’s research in:

Handwriting Examination: Meeting the Challenges of Science and the Law

Diana Harrison

Chief

Questioned Documents Unit

FBI Laboratory

Quantico, Virginia

Ted M. Burkes

Document Analyst/Forensic Examiner

Questioned Documents Unit

FBI Laboratory

Quantico, Virginia

Danielle P. Seiger

Supervisory Document Analyst/Forensic Examiner

Questioned Documents Unit

FBI Laboratory

Quantico, Virginia

http://www.fbi.gov/about-us/lab/forensic-science-communications/fsc/oct2009/Zbackup/Review/2009_10_review02.htm

It then then sets out key “Standards” that inform the approach taken by the FBI in Amerithrax. Compare the handwriting examination done in Amerithrax with the published standards (For example, compare E1658-08 with summary of handwriting opinion in Amerithrax Investigative Summary)

Standards

The Technical Working Group for Documents, now the Scientific Working Group for Questioned Documents (SWGDOC), was formed in 1997 to address the need for standards in the forensic document community. SWGDOC’s technical experts produce standards and submit them to ASTM International for ballot and eventual publication. ASTM is a voluntary standards development organization for technical standards for materials, products, systems, and services. The ASTM Committee E30 on Forensic Science was established in 1970 and consists of 10 technical subcommittees, one of which is the E30.02 Committee on Questioned Documents. Each standard submitted to ASTM is subjected to a rigorous review process by forensic document examiners and other forensic practitioners, as well as individuals with a general interest in the discipline. This review process ensures clear, concise, and high-quality standards.

To date, the forensic document discipline has published the following 18 standards through ASTM (see http://www.ASTM.org ). The two-digit number following the hyphen indicates the date of the standard and, as of this writing, is the most current standard available

• E444-09 Standard Guide for Scope of Work of Forensic Document Examiners.

********• E1422-05 Standard Guide for Test Methods for Forensic Writing Ink Comparison.*********

********• E1658-08 Standard Terminology for Expressing Conclusions of Forensic Document Examiners.*********

********• E1789-04 Standard Guide for Writing Ink Identification********

• E2195-02 Standard Terminology Relating to the Examination of Questioned Documents.

********

• E2290-07a Standard Guide for Examination of Handwritten Items.

• E2291-03 Standard Guide for Indentation Examinations.

• E2325-05 Standard Guide for Non-destructive Examination of Paper.

• E2331-04 Standard Guide for Examination of Altered Documents.

******** E2388-05 Standard Guide for Minimum Training Requirements for Forensic Document Examiners********

• E2389-05 Standard Guide for Examination of Documents Produced with Liquid Ink Jet Technology.

• ******** E2390-06 Standard Guide for Examination of Documents Produced with Toner Technology.********

• E2494-08 Standard Guide for Examination of Typewritten Items.

DXer said

http://www.buffalo.edu/news/releases/2002/07/5781.html

Handwriting Recognition Workshop Sponsored by UB to Focus on Forensic Uses, Including Anti-Terrorism

By Ellen Goldbaum

Release Date: July 17, 2002

BUFFALO, N.Y. — Investigators working to identify the source of the anthrax-containing envelopes that terrorized the American public last fall concluded they were hand-addressed by the same person. Messages penned in Urdu that allegedly belonged to Daniel Pearl’s kidnappers were introduced by prosecutors during their trial.

Expanding the forensic use of computer processing of handwriting to solve such high-profile criminal cases will be among the topics discussed at the Eighth International Workshop on Frontiers in Handwriting Recognition, sponsored by the University at Buffalo, to be held Aug. 6-8 in Niagara-on-the-Lake, Ontario.

The workshop will be attended by more than 100 computer scientists working in industrial, academic and government labs in 20 countries.

Interest in the use of computer processing of handwriting, once a field attractive to a small group of academic computer scientists and their counterparts in industry, has been on the increase for several reasons, said Sargur Srihari, Ph.D., SUNY Distinguished Professor in the UB Department of Computer Science and Engineering and director of UB’s Center of Excellence in Document Analysis and Recognition (CEDAR).

“In addition to continued expansion in the market for handheld computing devices, such as personal digital assistants, and improvements in offline recognition of handwriting for postal and financial applications, forensic uses for the computer processing of handwriting, especially in the wake of Sept. 11, are stimulating new areas of research,” he said.

The workshop will feature a panel discussion on Aug. 8 on computer processing of handwriting in forensic document examination. Panelists will include Srihari and representatives from the U.S. Secret Service and Federal Bureau of Investigations.

The workshop also will include sessions on using computational techniques to detect forgery; to recognize characters in foreign languages, such as Chinese and Arabic, and to determine the identity of a writer of a document, including work conducted in an independent analysis by Srihari that determined that the addresses on the envelopes containing anthrax likely were written by the same person.

“This is the first time this workshop is turning its attention to the computer processing of handwriting not just for recognition, to read what has been written, but also for analysis, to determine who wrote it,” said Srihari.

“In law enforcement in general that work still is being done by human analysts, but we now are beginning to use computers to do it. Teams at CEDAR and at other institutions that will be represented at the workshop are beginning to prove that automated analysis techniques can be quite successful.”

Srihari and his colleagues at CEDAR published a paper this month in the Journal of Forensic Sciences providing the first scientific proof that handwriting is unique to individuals. [see the erudite comment on that article and Professor Srihari’s reply]

***

More information on the workshop, including titles of papers, is available at http://www.cedar.buffalo.edu/IWFHR8/.

CEDAR is the largest research center in the world devoted to developing new technologies that can recognize and read handwriting. In the U.S., it is the only center in a university where researchers in artificial intelligence apply pattern-recognition techniques to the problem of reading handwriting.

Over the past decade, CEDAR has worked with the U.S. Postal Service developing and refining the software now in use in postal distribution centers across the nation that allow up to 70 percent of the handwritten addresses on envelopes to be read by sorting machines.

Conference sponsors include UB, CEDAR, Hitachi Ltd., Microsoft Corp., Motorola, Inc., Siemens AG.

– See more at: http://www.buffalo.edu/news/releases/2002/07/5781.html#sthash.KGtWAblQ.dpuf

DXer said

Professor Srihari gave an example from Amerithrax in a 2003 article:

A Survey of Computer Methods in Forensic Handwritten Document Examination

Sargur SRIHARI Graham LEEDHAM (2003)

Click to access igs2003paper.pdf

In recent years forensic document examiners in various countries, and particularly in the USA, have been seeking to strengthen their standing through Accreditation and Certification schemes, formalized training and other means (FSAB, 2003).

More recently, computer scientists have begun to apply various computer-vision and pattern recognition techniques that have been developed during the past 40 years [10], to the problems of writer identification and the authenticity/individuality of handwriting.

In this paper we review some the key techniques and results that have been published over the past few years in providing scientific support and computer-based tools to assist forensic document examination. This paper focuses on articles published in English, although it is recognized that some key relevant work is published in other languages. The paper is organized as follows. Section 1 is a description of studies concerning psycho-motor aspects of handwriting that have a bearing on forensic handwriting examination. Section 2 consists of work relevant to establishing the individuality of handwriting and studies establishing the expertise of handwriting examination. Section 3 describes computer-based tools that have been developed for use in forensic laboratories. Section 4 describes comprehensive systems that incorporate a variety of tools and procedures for document examination. Signature verification is dealt with separately in Section 5 due to its special nature and importance in document examination.

DXer said

Government accountability — and due process to men like Bruce Ivins and Hassan Diab — require that there be transparent and objective standards followed in the area of handwriting examinations.

The Buffalo News (New York)

May 20, 2014 Tuesday

Buffalo News Edition

FBI probes district’s handwriting ‘expert’

BYLINE: Deidre Williams and Sandra Tan; News Staff Reporters

The FBI is looking into the possibility that the “handwriting expert” Buffalo school officials cited in accusing a parent of faking her own signature on key documents may not have been an expert at all.

Instead, it appears the person the district used to clear itself was a retired police officer and private investigator with no expertise in handwriting analysis.

The controversy began last fall, when Timekia Jones, a parent at Harvey Austin School, accused school officials of forging her signature on key documents the district had to submit to the state to prove parental involvement. Parents asked the U.S. Attorney’s Office and the state Education Department to investigate.

DXer said

Professor Sriihari, S.N. ; CEDAR, SUNY – Univ. at Buffalo, Buffalo, NY, USA, in “Evaluating the Rarity of Handwriting Formations” explained that

Identifying unusual or unique characteristics of an observed sample in useful in forensics in general and handwriting analysis in particular. Rarity is formulated as the probability of letter formations characterized by a set of features. Modeling the distribution as a probabilistic graphical model several probabilities are inferred: the probability of random correspondence (PRC) as a measure of the discriminatory power of the characteristics, conditional PRC associated with a given sample and the probability of finding a similar one within tolerance in a database of given size.

In Amerithrax, among all writing samples submitted to Mr. Muehlberger, are there samples that contain all these elements:

a use of a dash instead of slash; a formalized one; downward sloping writing; and when writing in block-style letters, a slightly larger first letter?

Can Professor Srihari write software that searches for these four elements? Did he?

For those that USPIS lab director Muehlberger deemed “similar”, do they have some or all of these elements?

What percentage of writers write dates with a dash instead of a slash? What percentage write with downward sloping writing?

Alternatively, consider the most common pair of letters “th”. What would one learn from the pool of Amerithrax exemplars in regard to “th”?

Dr. Ivins’ “th” looks nothing like the “th” of the Amerithrax mailer.

See

Linguistic/Behavorial Analysis of the Anthrax Letters

November 9, 2001, Amerithrax Press Briefing

http://www.fbi.gov/about-us/history/famous-cases/anthrax-amerithrax/linguistic-behavorial-analysis-of-the-anthrax-letters

“The characteristics include:

1. The author uses dashes (“-“) in the writing of the date “09-11-01.” Many people use the slash (“/“) to separate the day/month/year.

2. In writing the number one, the author chooses to use a formalized, more detailed version. He writes it as “1” instead of the simple vertical line.

3. The author uses the words “can not,” when many people prefer to spell it as one word, “cannot.”

4. The author writes in all upper case block-style letters. However, the first letter of the first word of each sentence is written in slightly larger upper case lettering. Also, the first letter of all proper nouns (like names) is slightly larger. This is apparently the author’s way of indicating a word should be capitalized in upper case lettering. For whatever reason, he may not be comfortable or practiced in writing in lower case lettering.

5. The names and address on each envelope are noticeably tilted on a downward slant from left to right. This may be a characteristic seen on other envelopes he has sent.”

DXer said

See, e.g., The Annals of Applied Statistics Publication

Published by: Institute of Mathematical Statistics

CONSTRUCTION AND EVALUATION OF CLASSIFIERS FOR FORENSIC DOCUMENT ANALYSIS

In this study we illustrate a statistical approach to questioned document examination. Specifically, we consider the construction of three classifiers that predict the writer of a sample document based on categorical data. To evaluate these classifiers, we use a data set with a large number of writers and a small number of writing samples per writer. Since the resulting classifiers were found to have near perfect accuracy using leave-one-out cross validation, we propose a novel Bayesian-based cross-validation method for evaluating the classifiers.

Bibliographic Information(back to top)

CONSTRUCTION AND EVALUATION OF CLASSIFIERS FOR FORENSIC DOCUMENT ANALYSIS

Christopher P. Saunders, Linda J. Davis, Andrea C. Lamas, John J. Miller and Donald T. Gantz

The Annals of Applied Statistics

Vol. 5, No. 1 (March 2011) (pp. 381-399)

DXer said

IWBF 2014

2nd International Workshop on Biometrics and Forensics

27-28th March, Valletta, Malta

Quantifying Uncertainty in Forensic Identification

Sargur N. Srihari

SUNY Distinguished Professor

University at Buffalo, The State University of New York, USA

Abstract

Forensic identification is the task of determining whether or not observed evidence arose from a known source. The conclusion made by human forensic examiners is a choice among three opinions: identification/exclusion/no-opinion. Due to several court cases in which convictions have been over-turned due to the availability of additional evidence, the court system (judges and juries) have begun to expect a characterization of the confidence in the expressed forensic opinion. Today, in most forensic domains outside of DNA, it is not possible to make a probability statement since the necessary distributions cannot be computed with reasonable accuracy. This talk will describe methods for the evaluation of a likelihood ratio (LR) — the ratio of the joint probability of the evidence and source under the identification hypothesis (that the evidence came from the source) and under the exclusion hypothesis (that the evidence did not arise from the source). The joint probability approach is computationally and statistically infeasible. This is because the number of parameters is exponential with the number of variables used to represent the evidence and therefore statistical modeling and inference become intractable. We can replace the joint probability by another probability: that of (dis)imilarity between evidence and object under the two hypotheses. While this distance-based approach reduces to linear complexity with the number of variables, it is an oversimplification that results in significant inaccuracy. We propose third method, which decomposes the LR into a product of two factors, one based on distance and the other on rarity. The method has intuitive appeal since forensic examiners assign higher importance to rare attributes in the evidence and is also the principal method used by search engines in ranking web-pages. Theoretical discussions of the three approaches and empirical evaluations done with several data types (continuous features, binary features, multinomial and graph) will be described. Experiments with handwriting, footwear marks and fingerprints show that the distance and rarity method is significantly better than the distance only method.

DXer said

Some context of the FBI’s “Linguistic/Behavorial Analysis of the Anthrax Letters”:

Empirical evaluations of language-based author identification techniques

Carole E. Chaski Executive Director, Institute for Linguistic Evidence, Inc.

ABSTRACT Recent Court decisions in the United States call for the empirical testing of language-based author identification techniques.

Click to access Chaski_2001EmpiricalEvaluations.pdf

“THE TIMELY NEED FOR EMPIRICAL EVALUATIONS

***

In the early part of 2000, in the United States District Court, District of New Jersey, Roy Van Wyk was brought to trial for making threatening communications (United States v. Van Wyk, 83 F.Supp.2d 515, D.N.J., 2000). The Government, represented by Assistant US Attorney Charles B. McKenna, proposed that Special Agent James R. Fitzgerald of the Federal Bureau of Investigation be allowed to testify as an expert in forensic styl- istics (later text analysis) about the authorship of the threatening letters.1 The Government argued that Fitzgerald’s testimony should be admitted because it relied on McMenamin’s peer-reviewed publication (McMe- namin 1993), thus meeting at least one of the Daubert criteria which Federal judges must consider when determining the admissibility of evi- dence. Federal judges consider a variety of guidelines for admitting scientific and technical evidence; the Daubert criteria focus on the empirical reliability of a scientific technique.2 Thus, the Government argued that Fitzgerald’s technique should be admitted based on the fact that he relied on McMenamin (1993) which demonstrates the empirical reliability deducible from peer review before publication.

Defendant Van Wyk, represented by Assistant Federal Public Defender John H. Yauch, filed a motion in limine to exclude the proposed testimony of Agent Fitzgerald. The Defence argued that the ‘proffered expert tes- timony is subjective, unreliable and lacks measurable standards’ (Van Wyk, 83 F.Supp.2d 515, 521). Thus, the Defence argued that admitting forensic stylistics testimony would violate several other criteria of the Daubert standard of empirical reliability, such as falsifiability of the technique, known error rate, and standard operating procedures for performing the technique (see Note 2 for more discussion of admissibility factors).

The Court did, in fact, recognize the ‘lack of scientific reliability of forensic stylistics’:

Although Fitzgerald employed a particular methodology that may be subject to testing, neither Fitzgerald nor the Government has been able to identify a known rate of error, establish what amount of samples is necessary for an expert to be able to reach a conclusion as to probability of authorship, or pinpoint any meaningful peer review. Additionally, as Defendant argues, there is no universally recognized standard for certi- fying an individual as an expert in forensic stylistics.

(Van Wyk, 83 F.Supp.2d 515, 523)

The Van Wyk case and Judge Bassler’s ruling demonstrate the timely need for a sound and tested methodology for language-based author identification techniques.”

DXer said

I’ve been discussing the oft-cited article “Automatic handwriting recognition and writer matching on anthrax-related handwritten mail”

SN Srihari, S Lee – Frontiers in Handwriting Recognition, 2002.

GAO Should Obtain A Copy Of The FBI’s Handwriting Analysis Comparing The Letters To Atta’s

Posted by Lew Weinstein on January 22, 2012

Professor Srihari has served on the National Academy of Sciences Committee on Identifying the Needs of the Forensic Science Community (2007-08), the National Library of Medicine Board of Scientific Counselors (2001-07), the National Institute of Standards and Technologies’ Expert Working Group on Human Factors in Latent Print Analysis (2008-10). He has chaired committees of the International Association for Pattern Recognition. Srihari is an author of over 300 research papers, of which 65 are in journals (including one in the first issue of IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence) and seven United States patents. He has edited three books, and served as principal advisor to 36 doctoral students.

I am curious about other uses of pattern recognition. For example, last night at a party I learned that a man fond of automatic weapons who tried to take my Dad away by gunpoint has been released after serving 17 years for the crime.

It seems that the man, as tragically so often the case, risks a return to crime because of the nature of bad habits.

It seems that comparing bank robber photos using the expertise of someone like Dr. Srihari could be very fruiful.

Although there are some very neat graphics in article on handwriting examination and the anthrax letters — such as the 1’s and 0’s surrounding the “A” or the different “5s” — I don’t know how it compares to the technology used in facial recognition software. I like looking at bank robbery photos and often am stumped at making a comparison between two images.

On Wednesday the sheriff deputies caught someone at 5 a.m. at my favorite pizza parlor after a silent alarm went off.

The owner tells me he didn’t even have to get out of bed. The right technology can be a powerful tool.

DXer said

In the formal handwriting examination conducted for Amerithrax, it was concluded that Bruce Ivins probably did not write the anthrax letters.

Forensic Laboratory Examination Report

United States Postal inspection Service

Forensic Laboratory Services

224-33 Randolph Dr

Dulles, VA 20104-1000

March 08, 2007

USPlS\RJMuehlberger

Case No. – Lab File No. 9-957-002016

Type of Examination: Questioned Documents

Request Date(s) 1/2007

SA FBI Washington Field Office

7799 Leesburg Pike

Falls Church, VA 22043

PROBLEM:

ALL FBI

PEREII-I IS

DATE dlciil

Determine whether or not the questioned entries appearing in the printed digital images

(also contained on CD) of three labels; one depicting the writing “Ames strain RMR

from Dugway Bruce Ivins (1997) 2/27/02” and two

depicting the writing “Dugway Ames

spores – 1997” were written by Bruce E. Ivins, whose known writings are depicted in the

photocopies of various course of business documents.

Determine whether or not the questioned entries appearing in the printed diqital images

(also contained on CD) of two parcels; one addresse

second addressed

known writings are depicted in the photocopies ot

|and the

ere written by Bruce E. Ivins, whose

arious course of business documents.

Determine whether or not the questioned entries appearing on the “anthrax” envelopes and

letters (photographic copies retained in the laboratory) were written by Bruce E. lvins,

whose known writings are depicted in the photocopies of various course of business

documents.

FINDINGS:

Bruce E. Ivins probably wrote the original of the questioned entries appearing in the printed

digital images of the three labels described above.

Bruce E. Ivins probably wrote the original of the questioned address entries appearing in the

printed digital images of the two parcels.

Bruce E. Ivins probably did not write the writings appearing on the “anthrax” envelopes and

letters.

REMARKS:

The qualified findings expressed above are due to the lack of original documents from

which the examination and comparisons were conducted. The submission of the original

DXer said

In contrast, as my FOIA request, I submitted:

Record/Information Dissemination Section

Attn: FOIPA Request

170 Marcel Drive

Winchester, VA 22602-4843

Dear FOIA Officer:

Re: Closed Amerithrax case relating to Fall 2001 anthrax letters: Request for handwriting comparison for Bruce Ivins and Mohammed Atta

This is a request under the Freedom of Information Act.

Date range of request: September 25, 2001 to the present.

Description of Request: The report of handwriting experts, whether by the FBI’s Questioned Documents Units, or other experts, comparing the handwriting of the late Bruce Ivins and the late Mohammed Atta to the handwriting of the letters from Fall 2001 containing anthrax. The investigation into those letters is closed. Compare Barrett v. US, 2010 112259( “The Declaration of David Hardy, Section Chief of the Record/Information Dissemination Section of the FBI) Thus, exemption (b)(7) has no application.

Based on the FBI files at the FBI’s FOIA Reading Room, notice can be taken that both USAMRIID scientist Bruce Ivins and lead hijacker Mohammed Atta are dead and thus exemption (b)(6) has no application.

I am not asking that any documents not already in existence be created. Bartlett v. US, 867 F. Supp. 314 (E.D. Pa. 1994) (handwriting analysis must already exist and the FBI need not create such a record under FOIA).

Please search the FBI’s indices to the Central Records System for the information responsive to this request including but not limited to those related to: Bruce Ivins, Mohammed Atta, Amerithrax, anthrax, Questioned Documents Unit, handwriting comparisons, Kenneth Kohl (DOJ), Rachel Lieber (DOJ), Richard Lambert (FB), Edward Montooth (FBI), and Jason Bannan (FBI).

Please inform me if there will be any estimated fees before processing my request. I intend to upload the documents immediately to the “Case Closed” blog and amerithrax blogs that have several hundred thousand views and are forums where source documents are uploaded.

Bruce Ivins’ handwriting does not look anything like the letters containing the anthrax that was mailed and the Al Qaeda anthrax threat is continuing. Thus, I would ask that the request be expedited.

https://caseclosedbylewweinstein.wordpress.com

http://www.amerithraxwordpress.com

I am seeking information for personal use and not for commercial use.

Thank you for your consideration,

DXer said

The FBI, Secret Service, USPS can be expected to have available experienced experts given the volume of cases that require handwriting comparisons. Daubert applies. Without standards, if we allow anyone with access to a keyboard to opine, you get situations like the fellow who blogs daily on the subject of Amerithrax who has always insisted that it is 99% certain that a First Grader wrote the Fall 2001 anthrax letters! It’s not a simple matter of credentialism. It’s a matter of error rates in blind studies. A non-expert is not going to be heard to make such a comparison. See, e.g., Wolf v. Ramsey, 253 F. Supp. 2d 1323 (self-proclaimed handwriting expert was not qualified to provide reliable handwriting analysis where expert had never completed an accreditation course or been apprentice to a certified document examiner); Dracz v. American Generl Life Ins., , 426 F. Supp. 2d 1373, aff’d 201 F.d Appx 681 (where not certified by professional organization and trained by individual whose qualifications were suspect, individual was not qualified to render expert opinion in the field of handwriting analysis); Accord: A.V. By Versace, Inc. v. Gani Versace, 446 F. Supp. 252; American General Life and Acc. Ins. Co. v. Ward, 530 F.Supp. 2d 1306; E.E.O.C. v. Ethan Allen, Inc., 259 F. Supp. 2d 625 (N.D. Ohio 2003). The sensible approach to such an issue is to obtain the opinion of experts — such as is possible both under FOIA and pursuant to the ongoing being done by the GAO. The GAO also likely has its own experienced experts on handwriting.

DXer said

Prior to the closing, the material would be exempt under (b)(7). Moreover, material relating to a living person arguably would be exempt under (b)(6) [though the issue could be addressed by redaction]. And of course the FBI does not have to create records that don’t exist. Here, however, the reports by the FBI’s Questioned Documents Unit do in fact exist and are records subject to the Act.

WILLIAM C. BARTLETT v. UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF JUSTICE, FEDERAL BUREAU OF INVESTIGATION

CIVIL ACTION NO. 94-0836

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE EASTERN DISTRICT OF PENNSYLVANIA

867 F. Supp. 314

November 14, 1994, Filed

CASE SUMMARY:

PROCEDURAL POSTURE: Plaintiff brought an action claiming that defendant Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) had improperly withheld records from him in violation of the Freedom of Information Act (Act), 5 U.S.C.S. § 552. The FBI filed a motion to dismiss or in the alternative for summary judgment alleging that the court had no subject matter jurisdiction over the litigation.

OVERVIEW: The court agreed with the FBI’s contention that subject matter jurisdiction was lacking because no records requested by plaintiff had been located and because plaintiff’s requests were outside the scope of the Freedom of Information Act, 5 U.S.C.S. § 552. Plaintiff’s first request was for access to or copies of a report of forensic science handwriting examiners comparing the signature on his request under the Act with other records already in existence. The court held that to be subject to the Act, the requested record needed to be in existence at the time of the request; however, plaintiff was requesting the FBI to conduct a handwriting comparison and release the results to him. Therefore, because the request sought nonexistent material, it did not seek a record within the meaning of the Act.

DXer said

David Hardy, Section Chief of the Record/Information Dissemination section of the FBI has oft explained in Affidavits the difference between an open case and a closed case. for the purpose of applying exemption (b)(7):

For examplle in Barrett v. US, 2010 112259 the Court explained:

“The Declaration of David Hardy, Section Chief of the Record/Information Dissemination Section of the FBI, and correspondence from the Napa County Sheriff’s Department and San Francisco Police Department attached as exhibits thereto evidence that the Zodiac case investigation is ongoing, and Plaintiff [*8] has presented no admissible evidence that the investigation has been completed or is inactive. 1 (Hardy Decl. PP 11, 19, 27, Ex. D, Ex. E.) Therefore, Defendant has demonstrated the absence of a genuine issue of material fact as to the existence of an “enforcement proceeding” under Exemption 7(A).”

DXer said

Publication number 09-17 of the Laboratory Division of the Federal Bureau of Investigation is titled “Handwriting Examination: Meeting The Challenges of Science and the Law.” I commend it to the GAO’s attention. It is online. The AUSAs have tried to make a silk purse out of a sow’s ear just like the earnest FBI agent did in testifying against the Elvis impersonator in the ricin case. It is a case study of zealousness — but not anything approaching science or even an approach recognized as reliable under law.

The FBI provides the following references:

References

ASTM International. E2290-07a Standard Guide for Examination of Handwritten Items. ASTM International, West Conshohocken, Pennsylvania, 2007. Available: http://www.astm.org/Standards/E2290.htm.

Baker, J. N. Law of Disputed and Forged Documents. Michie, Charlottesville, Virginia,1955, p. 5758.

Baxendale, D. and Renshaw, I. D. The large-scale searching of handwriting samples, Journal of the Forensic Science Society (1979) 19:245251.

Beacom, M. S. A study of handwriting by twins and other persons of multiple births, Journal of Forensic Sciences (1960) 5:121131.

Boot, D. An investigation into the degree of similarity in the handwriting of identical and fraternal twins in New Zealand, Journal of the American Society of Questioned Document Examiners (1998) 1(2):7081.

Byrd, J. S. and Bertram, D. Form-blindness, Journal of Forensic Identification (2003) 53:315341.

Evett, I. W. and Totty, R. N. A study of the variation in the dimensions of genuine signatures, Journal of the Forensic Science Society (1985) 25:207215.

Federal Bureau of Investigation. Famous cases: The Weinberger kidnapping, FBI History [Online]. (n.d.). Available: http://www.fbi.gov/libref/historic/famcases/weinber/weinbernew.htm. Accessed August 25, 2009.

Federal Bureau of Investigation. Laboratory Division. Questioned Documents Unit Protocols. FBI Laboratory, Quantico, Virginia, 2007.

Gamble, D. The handwriting of identical twins, Canadian Society of Forensic Science Journal (1980) 13:1130.

Harvey, R. and Mitchell, R. M. The Nicola Brazier murder: The role of handwriting in a large-scale investigation, Journal of the Forensic Science Society (1973) 13:157168.

Hilton, O. Scientific Examination of Questioned Documents. Elsevier, New York, 1982, pp. 10, 17, 153157, 174.

Horton, R. A. A study of the occurrence of certain handwriting characteristics in a random population, International Journal of Forensic Document Examiners (1996) 2:95102.

Huber, R. A. The Uniqueness of Writing. Presented at the American Society of Questioned Document Examiners annual meeting, San Jose, California, 1990.

Huber, R. A. and Headrick A. M. Handwriting Identification: Facts and Fundamentals. CRC Press-Taylor & Francis, Boca Raton, Florida, 1999, pp. 1014.

Inman, K. and Rudin, N. Principles and Practice of Criminalistics: The Profession of Forensic Science. CRC Press-Taylor & Francis, Boca Raton, Florida, 2001, pp. 123125.

Keele, S. W. Movement control in skilled motor performance, Psychological Bulletin (1968) 70:387403.

Livingston, O. B. Frequency of certain characteristics in handwriting, pen-printing of two hundred people, Journal of Forensic Sciences (1963) 8:250258.

Muehlberger, R. J., Newman, K. W., Regent, J., and Wichmann, J. G. A statistical examination of selected handwriting characteristics, Journal of Forensic Sciences (1977) 22:206215.

Osborn, A. S. Questioned Documents. 2nd ed. Nelson-Hall, Chicago, 1929, pp. 205216, 226233, 247248, 363376.

Osborn, A. S. The Problem of Proof. 2nd ed. Nelson-Hall, Chicago, Illinois, 1975, pp. 491501.

Purdy, D. C. Identification of handwriting. In: Scientific Examination of Questioned Documents. 2nd ed. J. S. Kelly and B. S. Lindblom, Eds. CRC Press-Taylor & Francis, Boca Raton, Florida, 2006, p. 4774.

Rhodes, E. F. The implications of kinesthetic factors in forensic handwriting comparisons, Doctoral thesis, University of California at Berkeley, 1978.

Shiver, F. C. Case Report: The Individuality of Handwriting Demonstrated Through the Field Screening of 1000 Writers. Presented at the American Society of Questioned Document Examiners annual meeting, Washington, D.C., 1996.

Srihari, S. N., Cha, S.-H., Arora, H., and Lee, S. Individuality of handwriting, Journal of Forensic Sciences (2002) 47:856872.

Srihari, S., Huang, C., and Srinivasan, H. On the discriminability of the handwriting of twins, Journal of Forensic Sciences (2008) 53:430446.

DXer said

The handwriting analysis being withheld for Atta points to the writer of his Visa application and pilot school application as very possibly the mailer where the handwriting analysis for Bruce Ivins does not. An early article in the periodical Police Chief reporting on the opinions of the Secret Service lab helps understand some of the terminology used in such opinions.

NCJ Number: NCJ 053237

Title: LAYMAN’S GUIDE TO HANDWRITING OPINION TERMINOLOGY

Journal: POLICE CHIEF Volume:45 Issue:5 Dated:(MAY 1978) Pages:68-72

Author(s): T V MCALEXANDER

Corporate Author: International Assoc of Chiefs of Police

United States of America

Date Published: 1978

Page Count: 5

Type: Dictionary

Language: English

Country: United States of America

Annotation: THE HANDWRITING OPINION TERMINOLOGY USED BY THE U.S. SECRET SERVICE LABORATORY IS EXPLAINED IN LAY TERMS, AND REASONS WHY A HANDWRITING SAMPLE OFTEN CANNOT BE POSITIVELY IDENTIFIED ARE GIVEN.

Abstract: THE TERMS DEFINED ARE: POSITIVE IDENTIFICATION; HIGHLY PROBABLE, WHERE SOME CRITICAL FEATURE OR QUALITY IS MISSING; PROBABLE, WHERE BOTH SIGNIFICANT SIMILARITIES AND IRRECONCILABLE DIFFERENCES ARE PRESENT; INDICATION, WHICH MERELY SERVES TO KEEP THE PIECE OF EVIDENCE UNDER CONSIDERATION; NO EVIDENCE TO INDICATE, WHERE IT IS NOT LIKELY THE SUSPECT WROTE IT; AND POSITIVE ELIMINATION. VARIOUS PHRASES COMMONLY USED BY HANDWRITING EXAMINERS TO CONVEY EACH OF THESE IDEAS ARE DISCUSSED. REASONS FOR AN INCONCLUSIVE OPINION ARE EXPLAINED. THE HANDWRITING MAY LACK INDIVIDUALITY, TRANSITORY FACTORS MAY EFFECT IT, ACCIDENTAL FEATURES MAY APPEAR, IT MAY BE DISGUISED, GRADUAL CHANGES OCCUR IN WRITING HABITS OVER A PERIOD OF YEARS AND THE SAMPLES MAY NOT BE CONTEMPORANEOUS, IT MAY BE A TRACING OR COPY, AND THE SAMPLE MAY NOT HAVE THE SAME LETTER FORMS AND, THEREFORE, MAY NOT BE COMPARABLE. EACH FACTOR IS DISCUSSED. A GLOSSARY OF HANDWRITING EXAMINATION TERMS IS INCLUDED. (GLR)

Index Term(s): Forgery ; Handwriting analysis ; Expert witnesses ; US Secret Service

DXer said

The need for the reports from the FBI’s Questioned Documents Unit on the exemplars extends beyond handwriting analysis to the analysis of paper, the analysis of inks, the written instrument etc. There may be reports from other agencies helping, whether the CIA, USPS, Secret Service, or outside consultants.

INK: In the hundreds of pages of handwritten exemplars taken from Dr. Bruce Ivins’ home and office, FBI Laboratory Experts determined that there was not a single exemplar written by him in which the distinctive “fluid-like” ink used on the envelope was a match. FBI should produce the laboratory reports to GAO on the ink used in the first mailing (and the different ink used in the second mailing) without further delay.

PHOTOCOPIER TONER: In the hundreds of pages of photocopied exemplars taken from Dr. Bruce Ivins’ home and office, FBI Laboratory Experts determined that there was not a single piece of paper photocopied by him in which the same photocopy toner was used as in the letters containing the mailed anthrax. FBI should produce the laboratory reports to GAO on the photocopy toner used by the machine used to copy the letters without further delay.

Laboratory Analysis of Suspect Documents

APPROVED FOR RELEASE 1994

CIA HISTORICAL REVIEW PROGRAM

18 SEPT 95

https://www.cia.gov/library/center-for-the-study-of-intelligence/kent-csi/vol4no3/html/v04i3a05p_0001.htm

SECRET

Some of the possibilities, methods, and results of submitting written materials to examination by test tube and microscope.

LABORATORY ANALYSIS OF SUSPECT DOCUMENTS

James Van Stappen

Analysis of Paper

Although a document is legally defined as being of any material on which marks may be inscribed, including gravestones and in a recent case a silver goblet engraved with Josef Stalin’s true signature, the material used for most documents is of course paper. The laboratory analysis of paper must take into account its color and opacity, the size of the sheet, its weight and thickness, its fiber content, the direction of the grain, the finish, and the watermark. Comparison in these respects with exhaustive files of domestic and foreign paper stock samples serves to identify most papers. If the paper is a common, low-grade type, it will yield no clues to the originator of the document except perhaps his area of operation. But if it is a rarer and more expensive one, with few dealers and retail outlets, it may be possible to trace through these the limited number of people who had access to it. A unique paper may be, and in actual cases has been, traced to a single individual. The secret markings that identify paper used by governments, banks, and other official organizations are also many of them on file along with the paper stocks, as an aid in checking the authenticity of official documents.

It can be established that a document is forged by showing that its paper is not as old as its purported date. Sometimes the age of the paper can be determined from its composition or watermark, by referring to a file of manufacturers’ formulas and watermarks in use at different dates. More often it is necessary to measure the effects of age on its chemical content and color, taking into consideration the type of fiber in the paper and the climatic conditions under which it was stored. Using chemical reagents and a tintometer or similar instrument for gauging shades of color, the expert can usually determine the approximate age of the paper. If the paper has been artificially aged, a practice forgers often try, the age test will not be valid; but the false aging can often be detected and the document thus proved a forgery.

Analysis of Inks

The identification of an ink is begun by determining the type to which it belongs. The three chief types in use today are gallotannic (the most common), chromic, and aniline. Others are China ink, the colored vegetable-dye inks, a few dark ones like those made from wolfram and vanadium, and those for special application as for mimeograph and stamp pads. Chemical differences enable the laboratory to identify these types.

The age of the ink, which has the same bearing as paper age on the validity of a document, may sometimes be determined through data on file regarding changes in the manufacturers’ formulas. Waterman, for example, has changed formula four times in ten years, so that a sample of Waterman’s may often be associated with a particular period of manufacture. Another test is color. Permanent inks contain a temporary dye which soon fades, an iron and sulfur compound, and a weak acid. The action of the acid, oxygen, and humidity produces first a dark color and then over a period of years a slow fading to a weak stain. By using chemical reagents, the age of the ink can be approximated by comparing its color, taking into consideration the color of the paper, with standard color charts. If ink has been artificially aged the age test is impossible, but the induced aging itself is sometimes detectable.

Writing Instruments

When a stroke of ink writing is magnified fifteen or more times, the two tracks made by the point of the pen stand out much clearer than the line of ink between them. If the pen is new, the width of these tracks, compared with standard-brand widths shown in test charts, sometimes serves to identify the type of pen. When a well-worn pen has been used, the difference in width and appearance between the two tracks usually indicates whether the user is right- or left-handed. If a pen is worn badly enough, it may leave regular, easily identified scratches which provide positive identification of the very pen itself. The fact that most people fill their fountain pens with different kinds of ink at different times may also serve to identify an individual pen through the unique combination of inks in it.

The ball-point pen is more easily identified than an ordinary one. It uses a unique ink, there is a specific width of the ball point for each brand, and the surface of the ball, smooth as it may seem to the unaided eye, is really full of scratches which leave a pattern on the paper–the pen’s own fingerprints. Any non-standard type of pen is the more readily identified because of its scarcity.

If a document is written in pencil or crayon, the laboratory may be able to determine the formula of the material and through file comparisons perhaps identify the manufacturer. The age of pencil or crayon writing can be determined only as to whether it was done within the last ten or fifteen days. A unique or unusual pencil or crayon may possibly be traced to the individual who used it.

Identification of Handwriting

Handwriting, like other physical acts performed by adults, is characteristic of the individual writer; there is probably no act more characteristic of an adult than his writing. It can therefore be used for positive identification of the writer through comparison of the unknown specimen with known writings. This comparison is a matter not only of letter forms but also of many other characteristics, among them movement, muscular habits, pen position, line quality, shading, retrace, proportion, connections, spacing, and embellishments. If a sufficient number of similarities are found between a known handwriting and the questioned specimen, with no dissimilarities which cannot reasonably be accounted for, it can be concluded that both were written by the same person.

A person’s handwriting is developed by constant repetition over the years until it becomes second nature to him, a succession of deeply ingrained habits. The obstacles which confront a forger or a disguiser of his own writing are therefore manifold and great. It is practically impossible for a writer to divorce himself from certain inherent characteristics manifested in pressure points, pen lifts, the shading of strokes, etc., of which he is not even aware. In order to succeed in a forgery he needs not only to throw off his own characteristics but to assume the inherent characteristics manifested in another person’s writing, also a virtual impossibility. Handwriting comparison, however, should not be attempted by an amateur. Its most difficult aspect is evaluating the weight to be given each of the various distinguishing characteristics.

Typographical Identification

The identification of typewriting is similarly based on a sufficient combination of peculiar characteristics. Some of the more outstanding of these characteristics are the defects in type faces, the design of the type, misalignment due to mal-adjusted type bars, and uneven printing due to twisted type faces. The make and model of a typewriter can be determined by an examination of its product, and a used typewriter can be individually identified with certainty. Since manufacturers change type design from time to time, a document may also be proved fraudulent by showing that its type was not yet manufactured at the time of its purported date.

Aside from type design and the individual peculiarities of used type, the machine may be identified as one on which worn type has been removed and replaced with a new set. This new “retread type” may be distinguishable by its sharp, angular corners, by special retread designs, or by comparison with the type faces of the numerals, which get little use and are rarely changed, and therefore will not match the retread font used for the other characters.

It is occasionally possible to identify the individual who typed a document from his habit of using particular pressure on certain keys, making unique mistakes, and in some instances using unique spacings. If a suspect is made to type a dozen copies of the questioned document on the same machine, he will follow the same psychological patterns each time, and a comparison of the test specimens under magnification with the original document will make it apparent that they were typed by the same person. A person who uses the “hunt and peck” system, for example, characteristically hits the period so hard that he punctures or almost punctures the paper. Many people put much more pressure on combinations of letters found in their own names than on the other letters they type.

The Submission of Questioned Documents

The fruits of this analysis are available, of course, only when documents have been questioned or found suspect and submitted to the laboratory. This questioning is generally the obligation of the intelligence officer who first receives a document or of some staff analyst who finds that it does not fit well into the pattern of things already known about a case. The decision to request technical aid for analysis of written materials connected with an operation has in retrospect often turned out to be the most important decision made during its course. The use of this facility for counterintelligence purposes has been a steadily growing thing, for every find encourages other intelligence officers to bring dead files back to life for comparison with the newly identified material. Different areas have on numerous occasions found, when certain documents were compared, that they were host to the same adversary agent.

Many intelligence officers, however, still overlook the very evidence which might successfully terminate a case for them. It is often thought, for example, that a handwriting expert’s services are necessary only when a document is suspected of being forged, whereas the results of expert examination may be much more far-reaching in identification cases. The handwriting on an automobile ownership certificate, a piece of paper found at the scene of a meeting, an ink offset on a blotter, notations in a memorandum book, or any of a multitude of other writings may upon analysis prove to be of value to an operation. In clandestine operations where secret writing is used as a means of communications, it is often advisable to have the developed secret writing, as well as the cover letter, checked in the questioned document laboratory against the possibility that the agent has been killed, captured, or doubled and his communications taken over by the adversary. An earlier article in the Studies2 showed the value of this procedure also for the purpose of assessing the agent’s stability under strain.

In order to obtain a maximum benefit from the laboratory analysis, the intelligence officer should exercise great care in collecting and preserving the documents he submits. He should make every attempt to get samples of a suspect’s handwriting without his knowledge–his signature on pay vouchers, for example, or reports or letters in his natural writing. The highest quality of evidence is an uncontaminated original document. Anything less than that, such as a photocopy, is better than nothing, but still yields only qualified results. When it is known in advance that a document is to be submitted to the laboratory, it should be enclosed in a transparent plastic envelope large enough that folding is unnecessary. Thus protected, it can be read in transit on both sides and handled without soiling, wetting, or any physical alteration that might modify or destroy elements of the evidence.

This brief review should be sufficient to show that the science of questioned document analysis requires highly qualified professionals and, like surgery, should not be attempted by do-it-yourselfers. Among the cases on file that attest to the hazards of self-service in this matter is that of the 12-year-old paper mill cited above; it would have been detected at least two years sooner if the case officer involved had not imagined he could train himself in the technique. Even the experts employed in Washington are professionally impotent if separated from their standards, specimens, files, reference material, and technical facilities. Therefore this work cannot be done on a local basis in the field with any assurance of success.

DXer said

Here is an earlier copy of the FBI Handwriting Analysis Manual.

They Write Their Own Sentences: The FBI Handwriting Analysis Manual [Paperback]

F.B.I. (Author)

1.0 out of 5 stars See all reviews (1 customer review)

Book Description

Publication Date: October 1987 | ISBN-10: 0873644468 | ISBN-13: 978-0873644464 | Edition: illustrated edition

Everything put down on paper creates a unique image that can be traced, analyzed and reconstructed, revealing evidence unseen by the naked eye. FBI labs specialize in the study of handwriting, typewriting, rubber stamps, seals, printing methods, obliterations, alterations and charred paper. This manual reveals the methods used to follow the elusive paper trail, drawing on FBI case files.

DXer said

In contrast, Lew has taken the time over all these months to numerous lab notebook pages that demonstrate the lack of a match between Dr. Ivins and the handwriting in the Fall 2001 letters.

There’s not even been an attempt by anyone to explain why they think the exemplars uploaded by Lew — or any of the dozens available online — are similar to the writing in the letters containing the mailed anthrax.

No handwriting expert has put their reputation behind an Ivins Theory.

DXer said

To see how the FBI was approaching the issue of handwriting analysis we have the benefit of publication in Forensic Science Communications from 1999.

Then when the handwriting comparisons are produced by the FBI to GAO and made public, we can see how the FBI applied this learning to its Ivins Theory.

On Daubert generally, the NAS panel and Judge Harry Edwards of the Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia would respectfully disagree.

But I think everyone best get on the same page if in fact the same pages are shared.

http://www.fbi.gov/about-us/lab/forensic-science-communications/fsc/oct1999/abstrctd.htm

October 1999 Volume 1 Number 3

Presentations at the

2nd International Symposium on the

Forensic Examination of Questioned Documents

Albany, New York

June 14 – 18, 1999

http://www.fbi.gov/about-us/lab/forensic-science-communications/fsc/oct1999/abstrctd.htm

Proficiency Testing for Forensic Document Examiners

M. Kam

Drexel University

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

Proficiency tests for forensic document examiners (FDEs) were conducted for decades in different formats by employers of FDEs and various professional organizations. However, systematic tests of FDEs against control groups of lay persons were scarce until recently. Since 1994 (Kam et al. 1994), the Data Fusion Laboratory at Drexel University has designed, performed, and analyzed the results of several new tests of this kind. Among those were

• A test comparing handwritten documents to each other and deciding whether they were created by the same person (Kam et al. 1997).

• An incentive test measuring the effect of monetary incentives on the performance of lay persons in association of handwritten samples (Kam et al. 1998).

• A test authenticating signatures (Kam et al. in press).

• A most recent test associating photocopies with photocopiers.

The motivation for these tests was (and is) to determine whether FDEs provide solutions to handwriting and other document-related problems which are statistically different from the solutions provided by lay persons. (So far all our tests have shown that they do.) In addition, we are interested in quantifying the error rates of FDEs in solving document-related problems and comparing those to the error rates of lay persons. We recognize, however, that when estimating absolute error rates for FDEs using proficiency tests, we are likely to provide upper limits on true error rates in real practice. Unavoidable practical considerations limit the time we allow test takers to solve the problems, as well as the use of equipment, and the freedom to consult colleagues. Still, it is clear (Kam et al. 1994; Kam et al. 1997) that lay persons exhibit higher error rates than FDEs. In fact, we documented in our handwriting tests a general tendency of lay persons to match specimens that were created by different writers and declare that they were generated by the same person (over association).

The tests we have described in the literature so far do not lend themselves to test-taker by test-taker comparison, as each participant worked on a separate problem. In other words, these are not personal proficiency tests. They do, however, allow us to compare groups of test takers (such as FDEs versus lay persons and trainees against lay persons) to each other.

Some of the tests that we desire to conduct in the future will examine the following attributes:

• Elimination in comparison of handwriting.

• The effect of consultation of the conclusions of FDEs.

• Identification of different types of nongenuine signatures.

• Tests on disguise.

• Tests that determine the optimal or near-optimal degree of refinement in the opinion scales used by FDEs in expressing opinions.

A consistent long-term testing program will allow better understanding of FDEs’ abilities and limitations; will assist in the areas of standardization, training, and certification; and will develop a reliable body of data on the different aspects of FDE practice.

References

Kam, M., Wetstein, J., and Conn, R. Proficiency of professional document examiners in writer identification, Journal of Forensic Sciences (1994) 39:5-14.

Kam, M., Fielding, G., and Conn, R. Writer identification by professional document examiners, Journal of Forensic Sciences (1997) 42:778-786

Kam, M., Fielding, G., and Conn, R. Effects of monetary incentives on performance of nonprofessionals in document-examination proficiency tests, Journal of Forensic Sciences (1999) 43:1000-1004.

Kam, M., Gummadidala, K., Fielding, G., and Conn, R. Signature authentication by forensic document examiners, Journal of Forensic Sciences (in press).

****

Meeting the Daubert Challenge to Handwriting Evidence:

Preparing for a Daubert Hearing

A. A. Moenssens

University of Missouri

Kansas City, Missouri

Introduction

Daubert versus Merrell Dow Pharmaceuticals has been referred to as the villain, as the dragon that needs to be slain. But there is no need to be afraid of Daubert. The case is not going to result in the court excluding handwriting identification evidence, if you know what to prepare for when facing a Daubert hearing.

What is a Daubert hearing? It is, in effect, a minitrial within a trial, conducted before the judge only, not the jury, over the validity and admissibility of expert opinion testimony.

Today, preparing for a Daubert hearing presents less of a problem for questioned document examiners than it will pose in the near future for other branches of the forensic sciences such as firearms and toolmark examination, hairs and fibers comparisons, bitemark identifications, and other forensic disciplines. The advantage of having been first to endure the brunt of Daubert challenges also means you are ahead of the other forensic science disciplines, and you already are doing the kinds of things to overcome Daubert challenges that other disciplines are only beginning to think about.

Actually, of the trilogy of cases, Daubert, Joiner, and Kumho Tire, discussed at this symposium, Kumho Tire is perhaps even more important than Daubert because of two central points in that decision.

• It clearly states that a Daubert determination of reliability must be made in all cases where expert evidence is offered, whether we call it scientific evidence or technical knowledge or skilled professions.

• The Daubert inquiry is to be a flexible one. All of the factors identified inDaubert that guarantee the kind of reliability the Supreme Court said was needed for admissibility of opinions based upon scientific knowledge, such as replicability, established error rates, peer review, and so on, do not necessarily apply to all forms of expert testimony with the same rigor. They apply with full force only to those disciplines to which such factors can be applied. Conventional wisdom holds that these factors cannot be applied, in the manner spelled out in Daubert, to handwriting identification or to many other forensic sciences where cases deal with problems that are unique and where the accuracy of a specific finding cannot be stated with a measurable statistical degree of confidence.

Having said that, and as a matter of additional security and comfort to us, I believe that, today, the questioned document profession can meet the most stringent ofDaubert requirements.

The Criticism of Professors Saks, Risinger, and Denbeaux

You are all familiar with the comments that were made in the 1989 law review article. Despite all of the current and past research, the law professors-authors of the article are continuing to criticize forensic document examination dealing with handwriting comparisons for not having done the kind of research that they feel to be necessary to supply the larger legal community with empirical data on the validity of handwriting analyses. When they said so, in 1989, there was perhaps considerable truth to that. Not much published empirical research was readily available at that time. However, even in 1989, and assuming we ignore all the mistakes and errors of fact in the article, the criticism still was grossly unfair, because nothing in then-existing legal requirements established that such research be available for opinions on handwriting identifications to be admissible.

Not only had ample court precedent over nearly a century held that such opinion evidence was admissible, but there were statutes in several states and in the federal system authorizing or mandating admission (e.g., Rule 901 of the Federal Rules of Evidence). It was, therefore, unfair to ridicule a profession for not having done what the law had not required it to do.

What is more, prior to Daubert, admissibility of expert opinions was covered largely by the Frye test of general acceptance, and there is no question that handwriting identification testimony had been accepted universally by the forensic science communities globally. Questioned document examination evidence was clearly among what was called “scientific evidence” at a time when the Supreme Court, in Daubert, had not yet redefined the word “science” in such a way that its definition could only be applied to Newtonian physics. Earlier Supreme Court opinions, as had the opinions of every court of appeals and every state supreme court, had referred to all kinds of expert opinion testimony as “scientific” evidence even though, after 1993, ninety percent of those disciplines could not meet theDaubert Court’s test for what constitutes scientific knowledge.

Although it was unfair of Saks and company to criticize the questioned document profession for not having published the kind of basic research that no law required it to supply, it is even more unfair, today, for them to keep criticizing the discipline now that the research that they said should be done has been published and is continuing to be done with ever increasing intensity and frequency.

Dr. Saks and cocritics might very well have been lauded as heros for spurring the forensic document examination profession into supplying the necessary data that has since been published had they taken a more professional approach in alerting us to what they perceived to be the missing information and offered to aid and advise the profession. They chose, instead, to proceed as vengeful advocates in a vendetta war that they decided to wage against the prosecution and crime laboratories generally and document examiners in particular.

As I pointed out in my law review article rebutting their premises and their research, the critics’ overview of the profession was not only incomplete, often inaccurate, and their conclusion frequently based upon non sequiturs, but whatever deficiencies in document research they said they had discovered were expressed in a sarcastic manner, in demeaning and depreciating language, and in a nonprofessional manner that debased them more than it did the profession. They heaped further insult upon injury in comparing handwriting identification to tea-leaf reading and witchcraft. The tone of their critique was not the language of the disinterested scientist seeking to alert a professional community to deficiencies in their publication and research record so as to spur on the kind of research it would be desirable to have. Instead, from their premise that the skill of handwriting examiners who compare documents of questioned and known origin to determine common authorship lacked empirical justification, they chose to leap to an unwarranted next step, that such skill could not possibly exist.

Once having taken that position in print and as advocates in litigation, the critics now must feel compelled to continue to criticize handwriting identification as a profession despite the consistent results of past and ongoing research showing the fallacy of their arguments.

That is why the critics have forever lost the respect and the trust of decent, competent forensic scientists around the world. Although Dr. Saks is a social scientist, his coauthors have no credentials in that endeavor. In their attacks upon handwriting identification, all are advocates rather than scientists. Their pejorations are, and continue to be, advocacy rather than an objective and dispassionate legitimate critique.